City councillors Klassen and Skakun want to know why RCMP were at the official community plan meeting without their knowledge

Plus, that time the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers thought about flooding Prince George

So first things first a reminder of what’s going on: the city is reviewing its official community plan, which is kind of an aspirational planning document for the future of the city and its component parts. It’s not something that sets things in stones but it’s a general outline of where we, as a community, would like to go (a plan for the community, officially, as it were).

Over the course of multiple meetings and many hours, the real sticking point in this document has been the fate of the area surrounding Ginter’s Park. The Citizen’s city hall reporter Colin Slark wrote about the most recent meeting which lasted more than four hours on Wednesday, which ended with a number of amendments that will be continued at the next special meeting on April 16. I won’t get into all the details but the broad strokes are there’s a sense among a passionate group of participants that there are not enough protections in place for the green space around the city generally, and Ginter’s in particular. Anyways, here’s city councillor Trudy Klassen on X yesterday:

That was followed by this post from Brian Skakun in the Ginters Green Forever Facebook group:

That time the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Thought about flooding Prince George

I needed a second story for my newsletter today, so I started searching different forums and sites to see if anyone had made any posts bout the city recently. And boy did this one catch my eye:

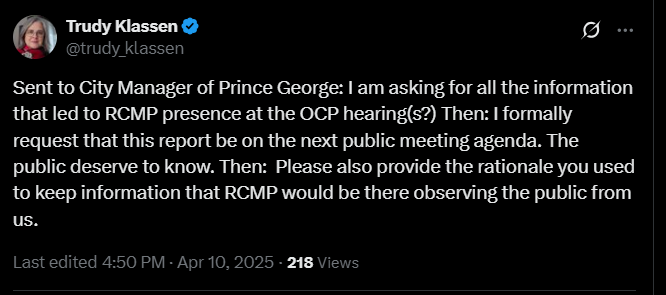

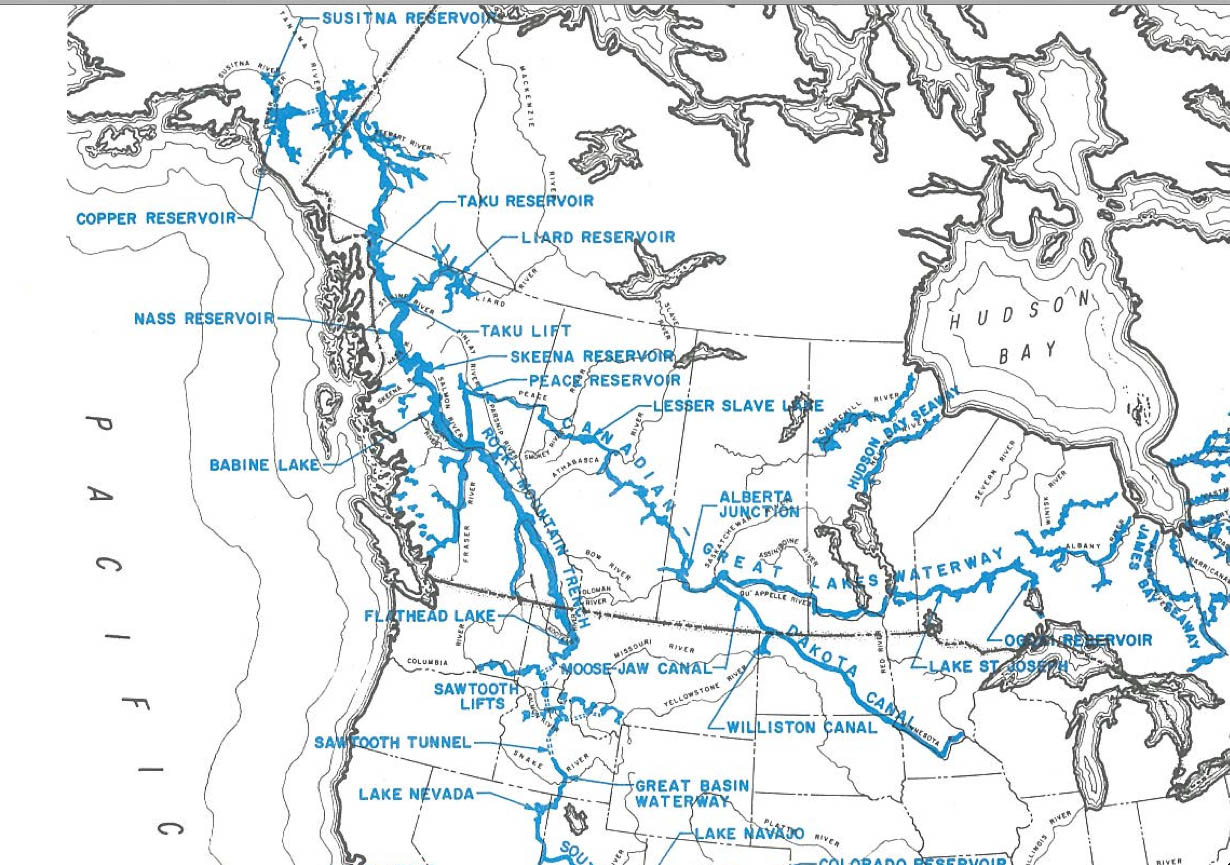

Unfamiliar with NAWAPA, I looked it up on Wikipedia like any good investigator. It stands for the North American Water and Power Alliance, and was

a proposed continental water management scheme conceived in the 1950s by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The planners envisioned diverting water from some rivers in Alaska south through Canada via the Rocky Mountain Trench and other routes to the US and would involve 369 separate construction projects. The water would enter the US in northern Montana. There it would be diverted to the headwaters of rivers such as the Colorado River and the Yellowstone River. Implementation of NAWAPA has not been seriously considered since the 1970s, due to the array of environmental, economic and diplomatic issues raised by the proposal.

Which is… a bit of an understatement.:

The Parsons plan would divert water from the Yukon, Liard and Peace River systems into the southern half of the Rocky Mountain Trench which would be dammed into a massive, 500 mi (805 km)-long reservoir. Some of the water would be sent east across central Canada to form a navigable waterway connecting Alberta to the Great Lakes with the additional benefit of stabilizing the Great Lakes' water level. The rest of the water would enter the United States in northern Montana, providing additional flow to the Columbia and Missouri–Mississippi river systems, and would be pumped over the Rocky Mountains via the Sawtooth Lifts in Idaho. From there, it would run south via aqueducts to the Colorado River and Rio Grande systems. Some of this water would be sent around the southern end of the Rockies in New Mexico and pumped north to the High Plains, stabilizing the Ogallala Aquifer. The increased flow of the Colorado River, meanwhile, would enter Mexico, allowing for greater development of agriculture in Baja California and Sonora.

At a costs of $100 billion US in 1970s dollars, the benefit of this, apparently, would have been to provide a whole bunch of water to areas that needed it across North America, plus a bunch of electricity. The downside was it needed nuclear explosions to build the trenchs and reservoirs at scale and, unfortunately, would have yes, flooded Prince George, as relayed in the book Cadillac Desert, a book by Marc Reisner on American policies towards the west publishe din the 1980s and which, it seems, was quite well received. Here’s the relevant passage:

It is Canada, however, that would have to suffer the worst of the environmental consequences, and they would be phenomenal. Luna Leopold, a professor of hydrology at the University of California at Berkeley, says of NAWAPA, “The environmental damage that would be caused by that damned thing can’t even be described. It could cause as much harm as all of the dam-building we have done in a hundred years.”

Every significant river between Anchorage and Vancouver would be dammed for power or water, or both—the Tanana, the Yukon, the Copper, the Taku, the Skeena, the Stikine, the Liard, the Bella Coola, the Dean, the Chilcotin, and the Fraser. All of these have prolific salmon fisheries, which would be largely, if not wholly, destroyed. (Since the extirpation of around 90 percent of the Columbia’s salmon run, the Fraser, the Stikine, and the Skeena have become the most important salmon rivers on earth.)

…

In Canada and the U.S. alike, not just rivers but an astounding amount of wilderness and wildlife habitat would be put under water, tens of millions of acres of it. Surface aqueducts and siphons—not to say hundred-mile reservoirs—would cut off migratory routes. Hundreds of thousands of people would have to be relocated; Prince George, B.C., population 150,000, would vanish from the face of the earth. In general, though, the project’s proponents display a peculiar blindness to the horrifying dislocation and natural destruction it would cause. They are far more comfortable talking about how NAWAPA is our only hope of averting worldwide famine.

My searches for mentions of this topic took me to a few other places, such as this blog post which makes mention of the plan, prompting this anonymous comment from a reader:

This is like a bad dream coming back to haunt me. I grew up in Prince George, BC which is located in the Rocky Mountain Trench (at the convergence of the Northern and Southern sections of the trench) and I remember this issue when I was a teenager in the 80’s. I remember my family receiving a letter or pamphlet in the mail from a local politician talking about the flooding of the Rocky Mountain Trench to provide water for thirsty folks down in California. I was horrified by the idea and the time and it haunts me to this day to think that this project could become a reality. During my search of websites concerning this project, I have not seen one that mentions the displacement of cities and towns of people living in the trench. From what I understand about the project (correct me if I’m wrong), my hometown and others would end up underwater and the residents would be forced to move. Not exactly the same scale as the Three Gorges Dam in China, but you get the idea. Why should some people have to lose their homes so that other folks can carry on life as usual on the edge of an arid desert? Not only would this project have a huge environmental impact, but a lot folks would lose out on the deal as well. When I was a teenager, our local politicians were looking out for our best interests, but I’m not sure if they are now.

I also found writer Nina Muntenau, whose book A Diary in the Age of Water, provides a fictional alternate history in which this plan came to pass. Here’s the excerpt she provides on her website, you can visit it to read more about her inspiration for it which involves a visit to the Ancient Cedar Rainforest:

Una stopped the car and we stared out across the longest reservoir in North America. What had once been a breathtaking view of the valley floor of the Rocky Mountain Trench was now a spectacular inland sea. It ran north-south over eight hundred kilometres and stretched several kilometres across to the foothills of the Cariboo Mountain Range. Una pointed to Mount Mica, Mount Pierre Elliot Trudeau and several other snow-covered peaks. They stood above the inland sea like sentinels of another time. Una then pointed down to what used to be Jackman Flats—mostly inundated along with McLellan River and the town of Valemont to the south. Hugging the shore of what was left of Jackman Flats was a tiny village. “That’s the new Tête Jaune Cache,” my mother told me.

If villages had karma this one was fated to drown over and over until it got it right. Once a bustling trading town on the Grand Trunk Pacific railway, Tête Jaune Cache drowned in the early 1900s when the Fraser naturally flooded. The village relocated to the junction of the original Yellowhead 16 and 5 Highways. Villagers settled close to where the Fraser, Tête Creek, and the McLellan River joined, all fed by the meltwater from the glaciers and icefields of the Premiere Range of the Cariboo Mountains. The village drowned again in 2025. I imagined the pool halls, restaurants, saloons and trading posts crushed by the flood.

“This area used to be a prime Chinook spawning ground,” Una said. “They swam over 1,200 km from the Pacific Ocean to lay their eggs right there.” She pointed to the cobalt blue water below us.

The reservoir sparkled in the sun like an ocean. Steep shores rose into majestic snow-capped mountains. The village lay in a kind of cruel paradise, I thought. It was surrounded by a multi-hued forest of Lodgepole pine, Western red cedar, Douglas fir, paper birch and trembling Aspen. Directly behind the village was Mount Terry Fox and across the Robson valley mouth, to the northeast, rose Mount Goslin. Behind it, Mount Robson cut a jagged pyramid against a stunning blue sky. Wispy clouds veiled its crown. I couldn’t help thinking it was the most beautiful place I’d seen. And yet, for all its beauty, the villagers had lost their principle livelihood and food. The reservoir had destroyed the wildlife habitats and the fishery. And its people with it.

Una pointed to where the giant reservoir snaked northwest and where towns like Dunster, McBride and Prince George lay submerged beneath a silent wall of water. Her eyes suddenly misted as she told me about Slim Creek Provincial Park, between what used to be Slim and Driscoll Creeks just northwest of what used to be the community of Urling. She told me about the Oroboreal rainforest, called an “Antique Rainforest”—ancient cedar-hemlock stands over a 1000 years old. She described how massive trunks the width of a small house once rose straight up toward a kinder sun. The Primordial Grove was once home to bears, the gray wolf, cougar, lynx, wolverine and ungulates. It was the last valley in North America where the grizzly bear once fished ocean-going salmon. Now even the salmon were no longer there, she said. Then she bent low beside me and pulled me close to her in a hug. She quietly said to me, “This is what killed Trudeau.”

I stared at her and firmly corrected, “but that was an accident.”

“Yes,” she agreed. Then added, “a planned one.”

Not for nothing, both Reisner in 1986 and Muntenau in 2000 take note of the fact that even if it’s not on such a grand scale, we have and are, in fact, flooding vast tracts of land for power and stripping others for forest resources. Anyways. Today I learned.

News roundup:

Dolleen Logan re-elected chief of Lheidli T’enneh First Nation.

At the Build the North conference, tough talk on tariffs and a bright future ahead.

PG Western Heritage Society makes pitch for rodeo grounds upgrades.

Miracle Theatre extends run of two comedies amid incredible audience turnout.

Northern Capital News is a free, daily newsletter about life in Prince George. Please consider subscribing or, if you have, sharing with someone else.

Send feedback by emailing northerncapitalnews@gmail.com. Find me online at akurjata.ca.

Well, I will need to add Nina Muntenau's book "A Diary in the Age of Water" to my reading list. Sounds like an emotional and deeply thoughtful piece. What an interesting, and terrifying, bit of local history. Thanks for sharing Andrew!

so, is the RCMP under obligation to tell anyone that they're attending a meeting? I don't think they need to, if they made the decision? If the city manager made the decision for *some* reason, that would be a different story.

Interesting. Intrigue!

(P.S. F**k the Americans. I'll have to read more on this "water scheme" now.)